Give Middle Housing a shot!

Matt Hutchins’ comprehensive discussion, at Medium, of the Washington state Model Code for Middle Housing and how we can have it produce more housing in line with HB1110.

In HB 1110, the State Legislature read the will of the people and demanded that we tackle the housing crisis more proactively by allowing Middle Housing in most cities and towns. Washington State Department of Commerce has created a basic zoning template that supersedes local code if town planners balk at updating their own code to comply. The draft version of that Middle Housing Model Code is out for comment (comment here by December 6th!). I have analyzed the real world implications of how it would regulate new housing and how we can tweak it to better support the creation of townhouses, flats, and infill development.

Here are my recommendations:

1. Allow Middle Housing to be larger than single family houses: more lot coverage, smaller setbacks, and make them taller.

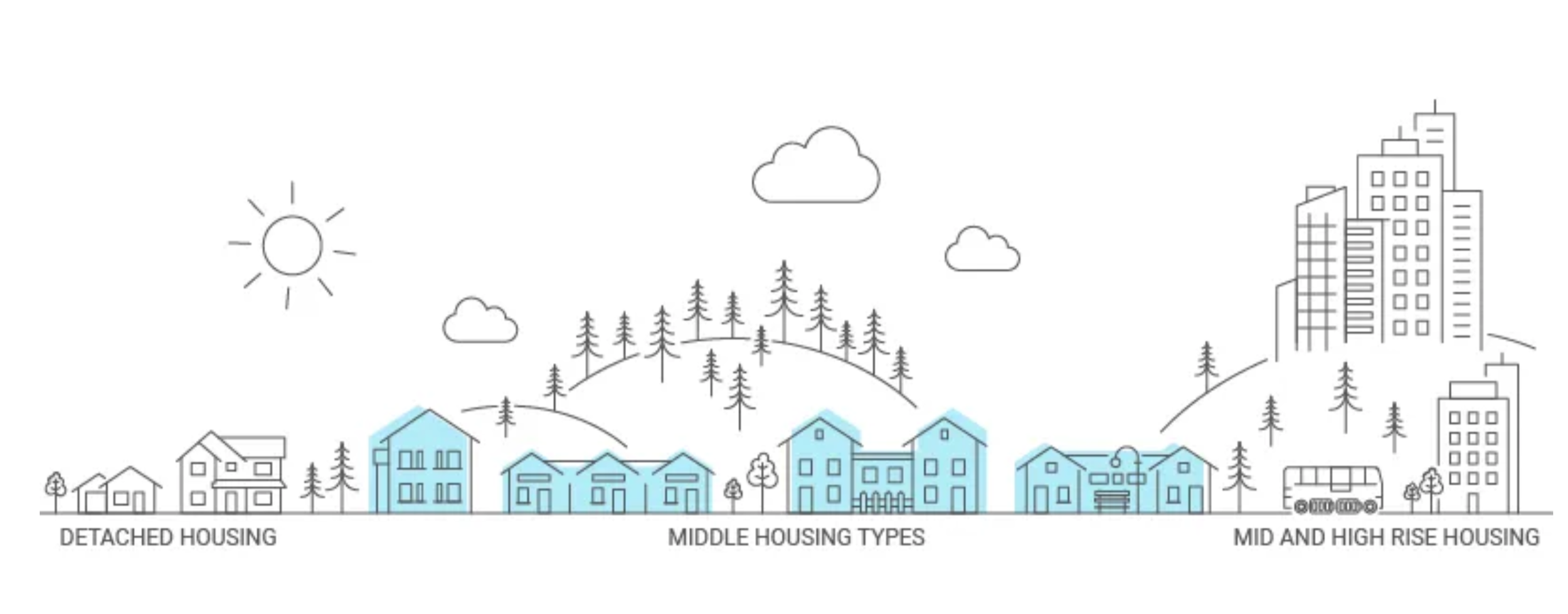

Diagram of current allowable single-family building sizes in 6 cities to illustrate that the Model Code’s Floor Area Ratio system is actually more restrictive.

It seems like an obvious point that the bulk of a building or buildings for up to 2, 4 or 6 households might be larger than one with just a single household, but a close look at some of the cities governed by this new legislation reveals that the draft code is MORE restrictive than current codes. It would effectively be a downzone in structure size in order to house more people. That isn’t a good trade, and for all the proof that Middle Housing has wide ranging benefits, we should have a code that supports it.

Middle housing is not just a bridge between the densities of single-family neighborhoods and denser areas, it is also a incremental increase in size between those building types.

2. Measure lot coverage, not FAR

There is a policy conversation about two methods for measuring building size: 1) lot coverage X height vs. 2) lot size X Floor Area Ratio. The draft code uses FAR for Tier 1 and 2 cities (the larger cities and the municipalities around them), and Lot Coverage for Tier 3 cities (smaller cities).

In the six Tier 1/Tier 2 cities I picked to analyze, five use lot coverage not FAR. The model code should follow suite. It is easy to implement, understand and compare apples to apples to existing codes.

Diagram of small cities buildable footprint illustrates how extra flexibility in lot coverage will translate to new housing for those communities.

Meanwhile Tier 3 cities, the code uses lot coverage to provide flexibility for how to develop successful infill housing, because lot coverage isn’t the critical threshold, the market is. I think this part of the Model Code will be actually be good for many smaller jurisdictions that are struggling with housing cost and access.

3. Set thresholds by looking at what can be feasibly built, not what might be politically expedient.

Illustration of all the new building types and whether they would be viable under the draft Model Code for typical lot sizes.

There is often a disconnect between how planners see development standards and how developers implement them. But ground truthing the code, when it is a draft, to understand the inevitable determinative impacts on the housing types that will get built, is the key to making the good development we want to see also the easiest to build.

Using a typical 5000 sf parcel zoned under the new code for 4 units, applying the FAR, we can build 4000sf. It becomes immediately apparent that many of the housing types we’re hoping for will never materialize and other types are going to yield less that then maximum number of units. Of the six types, I would expect the only feasible project is three townhomes. It is unlikely we’d generate very many 1000sf townhouses, 1200 sf triplex units or courtyard apartment buildings under the added cost of the IBC compliance.

The FAR needs to be up between 1 and 1.2 before we’d see the fourth townhome, or an apartment building.

4. Lean into making the most efficient and affordable housing form (small apartment buildings) the default infill Middle Housing type.

Our Spokane Six on the left works today, but wouldn’t be viable under the draft Model Code. This illustration shows that it would need to be 21% smaller.

Small apartment buildings have significant headwinds when it comes to financing, construction and operation. They also are the greenest, most efficient, context friendly and often least expensive forms of housing. They are also the best for preserving usable open space and landscape for large trees. They are the lowest common denominator building block for tackling the housing crisis. If the code works for those, then the other forms, like ownership townhouses, will work too.

When we tested our recent Spokane Grand sixplex, using the new Model Code, we discovered that we’d have to reduce the size by 21%, loose one of the porches, and downgrade the units from family friendly two bedrooms to one bedrooms. The pro forma for the development fell apart. If it can’t work in Spokane, with low land cost, reasonable construction cost, steadily climbing rents, there is very little chance these buildings would be viable in Puget Sound or other Tier 1 and 2 cities.

Without zoning incentives to build apartments, the market will continue to underproduce less expensive rental housing, even if we see some new ownership townhomes.

5. Reduce parking minimums.

Parking is always the cart that drives the horse. We have a housing problem not a parking problem.

So much has already be said and written about the high price of parking mandates, so I’m going to appeal to pure geometry.

On residential lots, designing for parking is step 1, before you even start to conceive of a building. For a sixplex on an alley, where parking is required, one space per unit arranged along the alley would require a lot width 56' feet minimum, which is wider than most urban lots. In order to provide the parking, much of the back yard is overtaken with pavement, more than 1/3rd of the site, lessening the quality of life for residents, creating stormwater issues and additional costs.

Without an alley, it is always worse; more than half of our typical lot is parking or driveway.

6. Regulating aesthetics on small neighborhood buildings is unnecessary micromanagement.

Strike this section. Or don’t. It is really so milquetoast that compliance isn’t an issue, but there will be lots of overlap/conflict with local codes that do regulate these simple aesthetics. Most townhouses are less that 20 feet wide — does a building’s design need to change every time there is a door? It is so fussy. In the interest of less bureaucracy, we should stamp out regulatory creep preemptively.

A Model Code that works.

The State’s Model Code is an opportunity to create a baseline for Middle Housing but it has to work. And this draft code would be so much more effective if it wasn’t second guessing its own mandate.

A final Model Code based on incremental increases of size over current single family structures, lot coverage not FAR, without parking minimums and design prescriptions, which allows builders the flexibility the make the homes people need, is the right direction forward for a statewide standard.

Hawthorne Hills Three:

Single-family residence, ADU & DADU

This project renovates an existing home and adds an attached accessory dwelling unit (AADU), and a detached accessory dwelling unit (DADU) to thoughtfully develop this single-family home into three rental units in the desirable Hawthorne Hills neighborhood of Seattle. It brings forward a model of urban density, providing much needed ‘missing middle’ housing. The exterior of the two buildings is unified in onyx-grey fiber cement siding with cedar accent areas. The home is 4-Star BuiltGreen certified.

The main home, with three bedrooms at 1,150SF, is renovated for modern living. The kitchen features three skylights that maximize natural light and brighten the core of the home. The original warm oak floors were refinished and unify the spaces.

The 410SF AADU takes advantage of the original house’s slightly set back position on the lot to build a new unit to the front and side setback. The entry opens to the bright kitchen and living space. Within the compact footprint, a hallway through the utility room leads to the bathroom and a separate bedroom.

The backyard cottage is a 1000SF two-story home. Situated on the lot for privacy, a private walkway leads to the front door. The DADU boasts three bedrooms with vaulted ceilings on the top floor. Downstairs, a generous great room and kitchen with expansive glass doors open to the patio and private backyard. The efficient, open plan and bonus storage add to the versatility of the home.

See more here.

TEAM

Builder: Cadre General Contractors

Civil: Davido Consulting Group/Watershed

Survey: Terrane

Structural Engineer: Owen Gould

GeoTechnical: Cobalt GeoSciences

Andersen Windows & Doors

Photography: Peter Bohler

WA State legislature passes SB 5491 single-stair bill

As we struggle with the construction cost of housing across the state and look to make building middle housing more affordable and abundant, the building code can sometimes add unnecessary complexity without adding any benefit to life safety.

In Seattle for the last fifty years or so, we’ve had a provision for small multifamily buildings that can eliminate one of the two typical stairs under very strict, prescriptive conditions: four units per floor, sprinklered buildings, fire-resistance-rated construction, quick access to a protected exit or to the street. These aren’t high rises or big apartment blocks.

Small apartment buildings should be the building block for middle housing and the single-stair provision makes many more sites feasible and gives architects more flexibility to design great buildings.

We have designed four of these small apartment buildings, varying from four to ten units. The sites are small urban infill, and a second stair would have probably killed the projects. On many infill sites, having a second stairwell means fewer windows for residents, fewer units, less ventilation, more blank exterior walls, and ultimately higher rent for residents because the buildings are much less efficient.

Senate Bill 5491 legalizes single-stair apartment buildings up to six stories. It will require the State Building Code Council (SBCC) to develop recommendations for these buildings and adopt the changes by July 2026.

The SBCC must convene a technical advisory group to recommend modifications and limitations to the International Building Code (IBC) that would allow for a single exit stairway to serve multifamily residential structures up to six stories.

The recommendations must include:

• considerations for adequate and available water supply

• the presence and response time of the fire department

• any other provisions necessary to ensure public health, safety, and general welfare

Six-to-twelve-plexes offer a superior urban experience, more housing units, more housing variety, and at least some fully accessible housing units. They also may preserve more tree canopy, increase open space, and optimize daylight compared to townhomes. These homes will push the bounds of the single-family envelope but maintain an urbanism-friendly street frontage.

As one of the region's leading voices for abundant and affordable housing choices, we advocate for smart density and missing middle housing. More efficient land use is critical to address our housing crisis, climate change, and persistent inequities in access to housing opportunities.

Statewide efforts to boost housing options make headway

This past legislative session, several bills made it through both houses and each will have long term benefits for the production of urban infill housing types such as cottages, ADUs, and small stacked apartment buildings.

HB 1337

The passing of HB 1337 expands housing options by easing barriers to the construction and use of ADUs.

· legalizes two ADUs per lot in any configuration of attached/detached

· legalizes an ADU on any lot size that’s legal for a house

· legalizes ADU size up to at least 1,000 SF

· legalizes ADU height up to 24 feet

· ends requirement for owner to live on site

· caps impact fees at 50% of those charged on houses

· lifts parking mandates within 1/2-mile or 15 minutes from transit stop

· prohibits design standards or other restrictions more stringent than what applies to the main house

· legalizes ADUs to abutting property lines on alleys

· legalizes ADUs in existing structures that violate current rules for setbacks or lot coverage

· prohibits requirements for public right of way improvements

· legalizes the sale of ADUs as condominiums

HB 1110

The Middle Housing Bill will mandate that medium and large cities create development standards for their lowest density zones to accommodate more housing. For Seattle, it means:

· Up to 4 units on any parcel not previously limited by an HOA or PUD.

· Up to 6 units on parcels that are within ½ mile (a 10 minute walk) of frequent or fixed transit

· Up to 6 units on any parcel if 2 are designated as affordable.

The form that these new housing types will be open ended, but the Department of Commerce is busy developing a model code for cities to use as a starting point. The deadline for cities to comply is 6 months after their next comprehensive plan cycle (for Seattle that is mid 2025).

As one of the region's leading voices for abundant and affordable housing choices, we have been advocating for backyard cottages—accessory dwelling units (ADUs)—since Seattle first considered them citywide in 2009.

More efficient land use is critical to address our housing crisis, climate change, and persistent inequities in access to housing opportunities. Modest infill houses like ADUs are a key strategy to empower citizens to provide new housing, build generational wealth, and leverage taxpayers’ investment in infrastructure, transit, schools, and parks.

A small building can have a big impact: this design has a commercial suite, a live work unit, two subsidized one bedroom apartments and two 2 bedroom apartments (with bonus lofts).

seattle architect has more missing middle housing on the boards

The housing crisis in California is so difficult in part because jurisdictions have opposed or slowly walked new housing through a mix of bad zoning and bureaucratic barriers. In response, the state has invoked a provision called the ‘builder’s remedy’ where towns and cities that have failed to show how they can meet their housing targets lose their ability to enforce their own zoning rules, provided that projects include some percentage of affordable housing.

The design is pushed to the street, preserving more backyard for residents and mature trees. The commercial space can be thought of as a cafe, retail or daycare.

As part of this zoning holiday we’ve designed this speculative small infill project. It has a commercial suite, a live work unit, two affordable one bedroom apartments and two 2 bedroom apartments with lofts.

Diagram of five unit apartment building.

This project is geared for using the Passive House green building standard to achieve very low operating expenses, and high indoor air quality. It is packed with amenities such as large porches and bike storage. If you are a developer interested in infill development or a property owner looking to make the most of this window of opportunity, please contact us at Matt@CASTarchitecture.com.

Seattle Architect pursues passive house certification with missing-middle housing on Lake Union

Echo on Eastlake apartments is pursuing Passive House certification, with early design and feasibility studies complete on the new 10-unit apartment building in Seattle’s Lake Union neighborhood.

This building will replace an existing single-family structure in this residential urban village, adding missing-middle housing. It utilizes the stacked flats concept which pushes the bounds of the single-family envelope but maintains an urbanism-friendly street frontage. There is one central stair and no shared walls. And, the two homes on the ground floor are both fully accessible.

Six-to-twelve-plexes offer a superior urban experience, more housing units, more housing variety, and at least some fully accessible housing units. They also may preserve more tree canopy, increase open space, and optimize daylight compared to townhomes.

More to come in the months ahead.

TEAM

Developer: West Crescent Advisors, LLC

Owner’s Representative: Woodworth Construction Management LLC @woodworth_built

Architect: CAST architecture

Builder: Carrig Construction

Civil Engineer: Davido Consulting Group

Landscape Architect: Karen Keist Landscape Architects

Arborist: Moss Studio

Geotechnical Engineer: Pangeo, Inc.

Surveyor: Terrane

Structural Engineer: Harriott Valentine Engineers

Envelope Consultant: B.E.E Consulting

Courtney W. Banker’s report Making “Plexible” Projects Possible includes research and examples from Seattle architect Matt Hutchins

Missing Middle Housing — Why Stacked Flats?

Stacked Flats push the bounds of the single-family envelope but maintain an urbanism-friendly street frontage. 6-/12-plexes offer a superior urban experience, more housing units, more housing variety, and at least some fully accessible housing units. In Matt Hutchins’s design approach, 6-/12-plexes also preserve more tree canopy, increase open space, and optimize daylight compared to townhomes.

Stacked flats can feature one or even four fully accessible units on the ground floor—without the need for an elevator (a significant cost too burdensome for most small-scale projects). They are a powerful incremental development strategy that can be replicated to result in substantial change, helping neighborhoods grow with more sustainable land uses, urban-supportive density, and accessible housing units.

This report builds on prior efforts to promote missing middle housing in Austin, Texas, leverages interviews with 23 local and national experts, and employs financial modeling of for-rent projects to identify the key barriers facing stacked flats.

The report is at the University of Texas Scholar Works: https://repositories.lib.utexas.edu/handle/2152/115590

@Courtney Banker

@Matt Hutchins AIA CPHD

Jansen Court missing-middle housing in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.

Seattle architect designs missing-middle housing

Jansen Court Apartments is a Built Green 4-Star 10-unit studio apartment building on the back of a 30’ parcel in Capitol Hill, preserving a turn-of-the-century house in the front yard.

With a single stair, this 4-story apartment building was quite the puzzle -- the complexity of regulations are magnified on a small project. Each level is different, with a basement, typical story, vaulted story, and unit with roof access. They're small, 400-600 SF, but nicely livable spaces.

And, it’s in Capitol Hill with a pretty street and bustling neighborhood. Walk Score: 92!

CAST is closely associated with efforts to improve housing affordability through increasing the “missing middle” moderate density infill within existing neighborhoods.

Photo credit: @lensit.studio

Reposted by permission of Sightline Institute

Author: Matt Hutchins (@HutchinsMatt)

A Seattle street showing the inclusion of more middle housing. Rendering by Matt Hutchins, used with permission.

matt hutchins, AIA, PHCD, INVITES CITIES AND TOWNS TO ZONE AND DESIGN FOR THE FUTURES THEY WANT

TAKEAWAYS

Seattle has concentrated several decades of population growth within narrow corridors of the city, disproportionately affecting poor and BIPOC communities while failing to ask nearby detached-house areas to evolve and grow as well.

Cities and towns with rising housing costs can address home shortages and inequities by opening up their zoning to new design options, as proposed by a middle housing bill that Washington state leaders are currently considering.

One such design: the Seattle Six, an attractive, economical, adaptable design that enhances neighborhood vibrancy and prioritizes quality of life, environmental responsibility, and anti-displacement. Cities and towns elsewhere can imitate or design their own such solutions.

If you want a healthy garden, you don’t blast just a couple plants with the hose; you water everything slowly so the roots can soak it up. Same with a city or town: sprinkle some housing everywhere, and you’ll get healthier neighborhoods.

Under Seattle’s Urban Village Growth Strategy the city has funneled 25 years of growth into tightly designated areas without asking adjacent detached-house areas to evolve as well. Along with America’s decades of racist redlining, car-centric design, and the primacy of detached-house building, this kind of strategy has limited what our cities can be. It has sent home prices skyrocketing, deepened racial inequities, and failed to address climate change in how we build our communities. Certain “gentle density” solutions like backyard cottages and townhomes have expanded housing options in tight markets, but for metro areas, the need is greater than these alone can address.

Fortunately, Washington legislators are currently considering a powerful “missing middle” housing bill that would open up a host of modest-sized housing options for people across the state while delivering numerous other benefits for communities. They are reworking zoning rules to empower us to build the future we want. And they are making it possible for architects like me to creatively contribute to the suite of design solutions that can help address the multiple challenges our cities and towns face.

INTRODUCING THE “SEATTLE SIX”

As an architect, I see how zoning regulations, good and bad, directly shape the design of buildings. Right now, there is a once in a generation opportunity to conceptualize the next basic building blocks of our towns and cities, starting from a set of key guiding values:

Healthier neighborhoods focused on quality of life

Adaptable site design and flexible home configurations

Deep green construction and inhabitation over a building’s life cycle

Centering anti-displacement

New possibilities for ownership, subsidized rentals, and more affordable housing

And while this design was developed specifically for Seattle’s typical lots and market, the values driving it are ones many Washington communities share. This is an invitation—and opportunity—for Washingtonians everywhere to imagine what could be possible in their own neighborhoods.

The “Seattle Six” is a three-story apartment building with six to ten households that fits on a range of typical residential lots. It has a compact form that is optimal for deep green building and observes the same height limits as Seattle’s Neighborhood Residential, Residential Small Lot, and Low-Rise 1 zones. In transit-rich areas, it can accommodate additional stories and units. With a floor area ratio (FAR) between 1.5 and 2.0, the Six is still small enough to bypass thresholds that trigger Seattle’s onerous Design Review. And finally, it proposes a clear direction for the urban design of streets and blocks that works in the short, medium, and long terms, aesthetically and economically.

HEALTHIER NEIGHBORHOODS FOCUSED ON QUALITY OF LIFE

The Seattle Six delivers a range of benefits for neighborhood vibrancy, connection, and attractiveness for residents both in and near Sixes. First, it energizes the sidewalk without overwhelming the street. By reducing the front setback to 12 feet but allowing stoops, covered porches, and balconies in an 8-foot-deep buffer, more residents have access to open space and a connection to life on the street. It replaces the idea of forced façade modulation with the option to embellish and individualize the building, while providing an amenity without complicating the basic structure. Overall, it is similar in height to currently allowed designs and recalls the classic small apartment buildings constructed in the decades before zoning strictures banned them from much of the city.

At the block level, over time, the Six establishes a land use pattern with well-defined urban edges and an interior courtyard in the backyards protected from noise, pollution, and street intrusions. It better preserves existing trees and makes room for new ones, a big advantage over typical oneplexes and townhomes, for instance, which slice up open space into narrow throughways or make backyards the only available land for new housing.

Speaking of backyards, the Six prioritizes access to larger rear yard open space, ample daylight, and options for big terraces for each flat. Units face both the street and the backyard, where kids can play or gardens can flourish, an improvement over another building across a narrow side yard. Residents cycling in will appreciate the design’s easy bike access, accommodating lockable individual bike storage at the ground floor and again in each unit.

Comparison between current and potential zoning envelopes for urban infill development. Illustration by Matt Hutchins, used with permission.

What’s more, on an everyday quality-of-life basis for people living in or near a Seattle Six, the benefits multiply. Because denser housing types bring in new families, one block with ten Seattle Sixes would have enough families with kids under five to justify a small daycare. Five more similar blocks would have enough customers for a successful café. Ten more, and you have a walkable/rollable neighborhood with local jobs, rapid transit, retail, services, and restaurants. At corners, the ground floor units could be live/work, corner stores, daycares, or cafes. Because it fits well with detached house neighborhoods, the Seattle Six can locate away from busy arterial streets and near to places like parks, schools, and libraries, bringing more vitality to every block.

How a block can grow. Top left: typical block of detached houses. Top right: typical townhouse development that would result in tree loss and inefficient use of open space. Bottom left: Ten Seattle Sixes sprinkled through the block. Bottom right: a full block of Seattle Sixes, showing how exchanging narrow side setbacks for larger back yards creates far more useable open space and more room for big trees. Illustrations by Matt Hutchins, used with permission.

In most cases, building a Seattle Six would require demolition of an older structure, just as a big new oneplex does today. This is exactly why Seattle should also allow alternative infill options like backyard ADUs and small-plexes that can coexist with older structures that remain in fine shape.

ADAPTABLE SITE DESIGN AND HOME CONFIGURATIONS

The Seattle Six supports a range of household sizes, multi-generational living, and moving within the building as life situations change. One can downsize and “age in place” or upsize as their family grows without having to give up the community of neighbors they’ve gotten to know.

Even on lots smaller than the 50’x100’ Seattle standard, the design is flexible enough to offer a variety of unit sizes. Floors can be a mix of family-sized one- and two-bedrooms; they can combine into one large multigenerational floor and later split into a principal flat and mother-in-law; or they can comprise a sprinkling of studios. A single central stair optimizes each floor for living space rather than the dark double-loaded corridors typical of larger apartment buildings. The version shown below is built on a concrete slab at grade level, but a partly below-grade floor of garden units would be practical depending on the topography.

The ground floor features accessible units via ramp, as well as a flexible studio. Residents can use it for a variety of purposes: for residents with temporary disabilities, housing a caretaker, or a short-term guest suite. Alternatively, it could be a common room, hosting things like teen game nights or get-togethers in a co-housing community.

DEEP GREEN CONSTRUCTION AND INHABITATION OVER A BUILDING’S LIFE CYCLE

Buildings are a major source of climate emissions, but they don’t have to be. They can incorporate deep green construction that reduces a building’s embodied and operational carbon.

To this end, the Seattle Six is conceived using Passive House principles in its design. The Six’s simple, compact form, continuous insulation to keep interiors comfortable at a consistent temperature, and shared party walls reduce energy loss, paying back residents with a lifetime of low heating and cooling demand. Paired with rooftop photovoltaic panels, the Seattle Six can be net zero energy.

Diagram of the Seattle Six’s green building features: Passive House, Net Zero, and Dowel Laminated Mass Timber. Illustration by Matt Hutchins, used with permission.

As for materials, the Six’s structure is designed with a dowel-laminated timber structure, which sequesters carbon and minimizes the need for concrete or steel, resulting in a low embodied carbon construction. The mass timber party walls and stair core satisfy the fire resistance rating. And bonus: it can be remanufactured for use in a future project as part of a more circular economy.

The Six also accounts for its region’s natural environment. Its green roof and on-site storm water management limits runoff from the site. And as wildfire smoke becomes more commonplace, the Six’s heating recovery ventilation system not only saves energy but filters pollutants to supply fresh air throughout the building.

COUNTERING DISPLACEMENT

The goal of Seattle’s Urban Village growth strategy was to concentrate new housing around commercial centers and serve them with an expanded transit network. But the strategy’s zoning changes disproportionately landed on poor or BIPOC neighborhoods, such as the Rainier Valley. The consequence has often been a cycle of speculation, displacement, and gentrification at the expense of people who’ve built their lives there.

Having a small apartment building that can plug in anywhere, starting in areas the city characterizes as having “low displacement risk” (i.e., most residents have the means to stay in their homes or find other housing nearby), would reduce the pressure on housing in other, less expensive areas. In a city like Seattle that’s adding lots of jobs, building lots of homes is essential—and the Six is a template for every neighborhood to do its part.

Allowing six or more households to divvy up the cost of Seattle’s pricey land lowers housing costs, too. Efficient, modern buildings like the Six would offer a mid-sized and mid-priced option between detached houses or townhouses on the one hand and large apartment buildings on the other. Indeed, Sightline recently analyzed possible development scenarios under Portland’s new zoning code. It found that new triplexes and fourplexes weren’t quite financially viable there in most cases, but that sixplexes in Seattle’s more expensive market might be.

In other words, the Seattle Six fights displacement in exactly the same way it fights segregation: it creates a new, cheaper way for people to live near jobs, parks, schools, and good public transit while reducing development pressure on other vulnerable neighborhoods.

NEW POSSIBILITIES FOR OWNERSHIP, SUBSIDIZED RENTALS, AND MORE AFFORDABLE HOUSING

We’ve underproduced housing for nearly a generation, putting even the most modest starter home beyond the reach of most Washingtonians. In just a decade, the state’s median home price has increased by 237%. Rents are on a similar trajectory, rising 183% for a two-bedroom apartment over the same period.

Whatever form new development takes, we’ll also need creative forms of ownership: co-ops, urban co-housing, and condos, for example. One interesting idea well suited for Seattle is the Polykatoikia, where landowners who are cash-poor but land-rich negotiate with a developer to swap a new apartment building on their land in exchange for a flat or flats in that new building. It is an excellent way for local landowners to maintain and grow generational wealth, stay in their neighborhoods, and create new homes in the process.

The “polykatoikia” idea, or housing swap, by which a homeowner can support new housing, maintain ownership, and resist gentrification. Illustration by Matt Hutchins, used with permission.

To the south, Portland’s Residential Infill Project allows developers to build extra units in exchange for affordable housing. The Seattle Six framework could easily support more households, too: either with an extra floor or a smaller height limit bonus to add a level of garden suites. Seattle’s Mandatory Housing Affordability performance option won’t help private developers create on-site affordable units given the small scale, but perhaps some of the MHA payments taken in by the Office of Housing could be deployed to finance small apartments, similar to how the Equitable Development Initiative has been supporting anti-displacement efforts.

BUILDING THE TOMORROW WE WANT, TODAY

It is a watershed moment for Washington: an opportunity in our housing policy to address climate change and racial inequities while building the homes we need and communities we want. The Seattle Six is just one model of how that might look. It’s also an invitation, as state leaders consider critical middle housing legislation, for communities across the state to boldly envision the future they want and build it into reality.

Matt Hutchins is a principal at CAST architecture, specializing in creative urban infill, affordable housing, green building, and shaping land use policy. He serves on the Seattle Planning Commission and as the Director of Public Policy for AIA Seattle. He is a Certified Passive House Designer. Find him on Twitter at @HutchinsMatt.